Uncategorized

A slight sting: Malaria mosquito or vaccine?

“As a malaria researcher, I used to dream of the day we would have a safe and effective vaccine against malaria,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization Director-General. “Now we have two.”

The first ever malaria vaccine was approved in October 2021. Now, a research team at Oxford University has developed a second vaccine for malaria. This vaccine was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in October 2023 and is now being used in high malaria-risk countries.

| Malaria: some history

Did you know that the Gin & Tonic was originally used for malaria prevention? In the 1700s a doctor discovered that tonic contains a substance (quinine) that can be used to treat malaria. Gin was first added in the 1800s to make the bitter tonic slightly more palatable. Nowadays, tonic contains very little quinine and better medicines have been developed.

Source: Library of Congress, US |

The development of the first vaccine was a great start. However, the demand for malaria vaccines is very high. Production of that vaccine simply couldn’t keep up. That is why the discovery of a second vaccine is terrific news. Furthermore, the second vaccine is cheaper to produce. But why did it take so long to produce a vaccine in the first place?

Let’s begin by taking a closer look at malaria. It is caused by a parasite which infects mosquitos. When humans are bitten by an infected mosquito, the parasite spreads through their blood. Mild symptoms of malaria include fever, chills, and headache. Severe symptoms, such as seizures and difficulty with breathing, can become life-threatening if left untreated. That is why good treatment and prevention is essential.

The spreader of malaria: a female Anopheles mosquito

Source: National Science Foundation

However, developing a vaccine against malaria is tricky. “It is a very clever parasite,” says Dr. Blandine Franke-Fayard, head of the molecular malaria vaccine research team at Leiden University Medical Centre. This explains why it has taken this long to develop a vaccine. According to Dr. Franke-Fayard, the parasite hides in our own cells most of the time. This makes it very difficult for our immune system to recognize and attack the parasite.

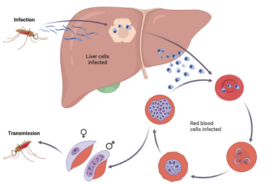

There is another reason why malaria is so difficult: the parasite has a very complex lifecycle. It invades different types of cells. Furthermore, it takes on multiple distinct forms within the human body. To the immune system, all these forms are different entities to be recognized. This makes it difficult to choose a vaccine target. For more information on this, see the Immune system and vaccines textbox.

Malaria parasite lifecycle

Text box:

Immune system and vaccines

An important component of our immune systems is antibodies. These molecules help your body to fight of infections. Each antibody is specific to one pathogen, be it a virus, bacterium, or parasite. Antibodies recognize a pathogen by binding to an antigen, which is a part of a pathogen.

Vaccines work by introducing your immune system to an antigen without the risk of getting truly sick. There are different strategies for this, including using only part of a pathogen or a weakened pathogen. The trick is to choose a good vaccine target.

In the case of malaria, each stage in the life cycle has different antigens. Your immune system may recognize the parasite in the first stage. However, if just a few parasites escape and enter the second stage, your body no longer recognizes them. Then you can get sick.

This complex lifecycle also explains why people in endemic areas are never fully immune, says Dr. Franke-Fayard. Their immune system might recognize the parasite in one stage, but as soon as it moves on it is no longer on the radar. This makes it very hard for your immune system to fight off infection completely.

This difficulty can also be seen in the numbers. In 2022, there were an estimated 608 000 malaria deaths worldwide. More than one thousand children died every day due to malaria. The heaviest burden is in WHO’s African Region, making malaria one of the continent’s biggest early childhood killers.

And the malaria-risk regions may be increasing. “The changing climate poses a substantial risk to progress against malaria,” said Dr Ghebreyesus. Global warming will allow the mosquito to spread to regions where it currently doesn’t reside. Furthermore, the rising temperature results in a longer mosquito season. This increases the time during which people may get bitten. Lastly, climate change is increasing the incidence of extreme weather events. Heatwaves, extreme rainfall, and flooding are all examples of events that pave the way for mosquitoes.

“Sustainable and resilient malaria responses are needed now more than ever.”

Dr. Ghebreyesus

This is where a vaccine provides hope. “There is a huge vaccination campaign starting now, but we have to see in the long term what the results are,” says Dr. Franke-Fayard. “The current vaccines have just one target, and that may not be enough. That is why we thought to create a genetically modified parasite,” she explains in relation to her own research. This parasite can only go through the first stage of development, after which it dies. This allows people to become immune without the risk of getting sick.

Currently, we seem to be one step ahead of the parasite. Research continues in order to understand more about malaria and about how the vaccines work. And researchers keep working on new vaccines to stay ahead. Meanwhile though, this milestone is definitely cause for celebration. “This second vaccine is a vital additional tool to protect more children faster,” says Dr. Ghebreyesus. “It brings us closer to our vision of a malaria-free future.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.