Oceanic Acidification

Ocean Acidification: Can We See the Future?

Ocean acidification

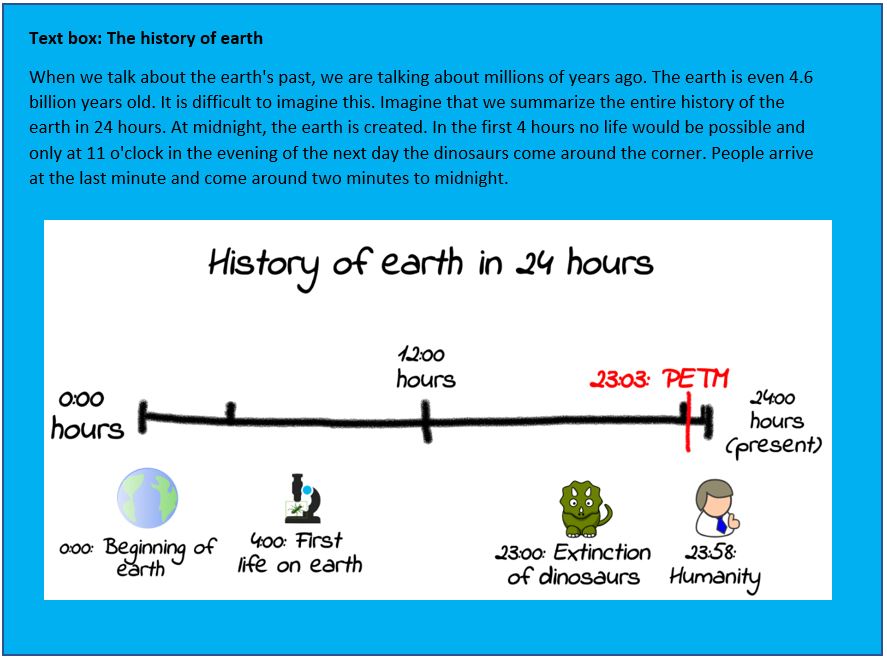

Right now the oceans are acidifying. This has major consequences for the animals that live in the ocean. This also has major consequences for us as humans, a large part of our food comes from the oceans. If less can live in it, some of our food sources will be lost. It is not the first time that the oceans acidify, long before there were people on earth, it also happened. How did this happen then? And what were the consequences? By looking back at these events, we can hopefully learn something about our future.

We look back

Ocean acidification is a result of a higher amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Much CO2 enters the ocean from the air and makes it more acidic. The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has never been constant in the past. Due to volcanic eruptions, among other things, there have been many periods in the history of the planet where there was a lot of CO2 in the air. Around those times the oceans have also become acidified, in the same way as they are now. Now that ocean acidification is taking place again, we can use the lessons from these periods to see what possible consequences could be. What’s the same this time, and what’s different?

In the history of the earth there have been enormous differences in climate, amount of CO2 and acidification of the oceans. Of course, people who study contemporary ocean acidification cannot conduct experiments on Earth. If we want to know what the consequences will be of a lot of CO2 in the air, we can therefore look at periods in the past when there was also a lot of CO2.

The PETM

One of those periods that is very similar in terms of CO2 levels to today is also called the Paleo-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). “During PETM, the climate warmed up enormously as greenhouse gases increased in the atmosphere,” says Ilja Kocken, paleoceanographer and climate expert at Utrecht University. “Of course that is happening now, so we can learn a lot by studying this.”

The PETM was 56 million years ago, about 10 million years after the dinosaurs (or 3 minutes later on the 24-hour scale). During this period, due to volcanism, a lot of CO2 was released into the atmosphere very quickly. The PETM has had a major impact on all life on Earth and the oceans became acidic. As a result, half of all micro-organisms that live on the soil have died out.

“We cannot do experiments in climate sciences like you can do in other sciences,” Ilja continues. “In physics, for example, you can set up an experiment to learn what causes and effects are. This is not possible with the climate because it takes too long and is too complicated. We can look to the past, where natural changes have taken place that we can see as natural experiments. If we study how the climate reacted 56 million years ago when such a natural experiment took place, we can learn about what lies ahead in future climate change. ”

Since the industrial revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, humanity has emitted about 1.5 trillion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. To be clear, that is 1,500,000,000,000,000 kilos of CO2. This enormous amount of CO2 was released at a rate ten times higher than during the PETM. As a result, scientists see that the same thing is happening right now as then.

Small shellfish in particular have a hard time with ocean acidification, it is more difficult for them to make their shells under acidic conditions. These animals largely serve as food for larger animals and this can become a major problem for the entire food chain. This, coupled with overfishing and pollution, puts a lot of pressure on the oceans in our time.

The end of the PETM came after 200 thousand years. As now, the surplus CO2 in the atmosphere was then absorbed by the oceans. Part of this absorbed CO2 then ends up under the seabed. This is the only way in which CO2 can be removed from the air for a longer period of time. (For more information see our blog post: “There’s something in the water”). Trees and plants also absorb CO2, but when they die they are burned or eaten by bacteria. As a result, that CO2 is released back into the air relatively quickly. Once CO2 is in the seabed, we really lose it for a long time (millions of years).

And now?

The situation today is therefore very similar to 56 million years ago. But one very important thing is different. The Earth is now inhabited by humans. These people are not only the cause of the problem, but they are also aware that ocean acidification is going on. Man also has the power to do something about this. The environmental situation is very worrying and it is difficult for scientists to make precise predictions. After my conversation with Ilja I ask him how he is doing. “It’s very easy to give up,” he replies. “I believe the strength is in uncertainty. We know very little for sure, so it may not be too bad. In that case, we will have to do double our best, because we may not be too late to save the climate. We cannot miss that opportunity. ”

Sources / Contacts

Garrison, T. (2013). Eceanography, An Invitation to Marine Science. (8th edition).

Hönisch, B., Ridgwell, A., Schmidt, D. N., Thomas, E., Gibbs, S. J., Sluijs, A., … & Kiessling, W. (2012). The geological record of ocean acidification. science, 335(6072), 1058-1063.

Johnson, S., 2020. Ocean Acidification On Track To Be Among The Worst Of The Last 300 Million Years. [online] Ars Technica. Available at: <https://arstechnica.com/science/2012/03/ocean-acidification-could-become-worst-in-at-least-300-million-years/> [Accessed 17 September 2020].

Kump, L. R., Bralower, T. J., & Ridgwell, A. (2009). Ocean acidification in deep time. Oceanography, 22(4), 94-107.

Nash, M (2008), Back to the future. HighCountryNews

Rudiman, W.F. (2014). Earth’s Climate, past and future.(Third edition). Middle Tennessee State University, USA: Macmillan education.

Veron, J. E. (2011). Ocean acidification and coral reefs: an emerging big picture. Diversity, 3(2), 262-274.

Kocken, Ilja. PhD candidate of Geosciences, Earth Sciences and Stratigraphy & paleontology. Utrecht University.