21st Century Doctors

What do Corona apps do with your data?

Pretty much as soon as the coronavirus pandemic started, it became clear that countries could not handle contact tracing; they did not have the capacity to call all the people that had been in contact with an infected person. In order to apply contact tracing more efficiently, many countries started to develop their own corona app.

Recently, in the press conference on October 13th, Dutch Minister of Health, Hugo de Jonge, said that contract tracing with the current number of corona infections was “bijna onmogelijk” [almost impossible], due to the “bizar hoge aantallen” [ridiculously high numbers]. Now that we’re deep in the second wave of infections, it might be the time to take another look at our own Dutch corona app, CoronaMelder. But how does it work exactly? And could the app be the solution that prevents a full lockdown?

How do these corona apps work?

Most corona apps use bluetooth tracking. Countries like Germany, France, Italy, Canada, Australia and also the Netherlands all have corona apps that use this technology.

A government advertisement for the Dutch CoronaMelder app.

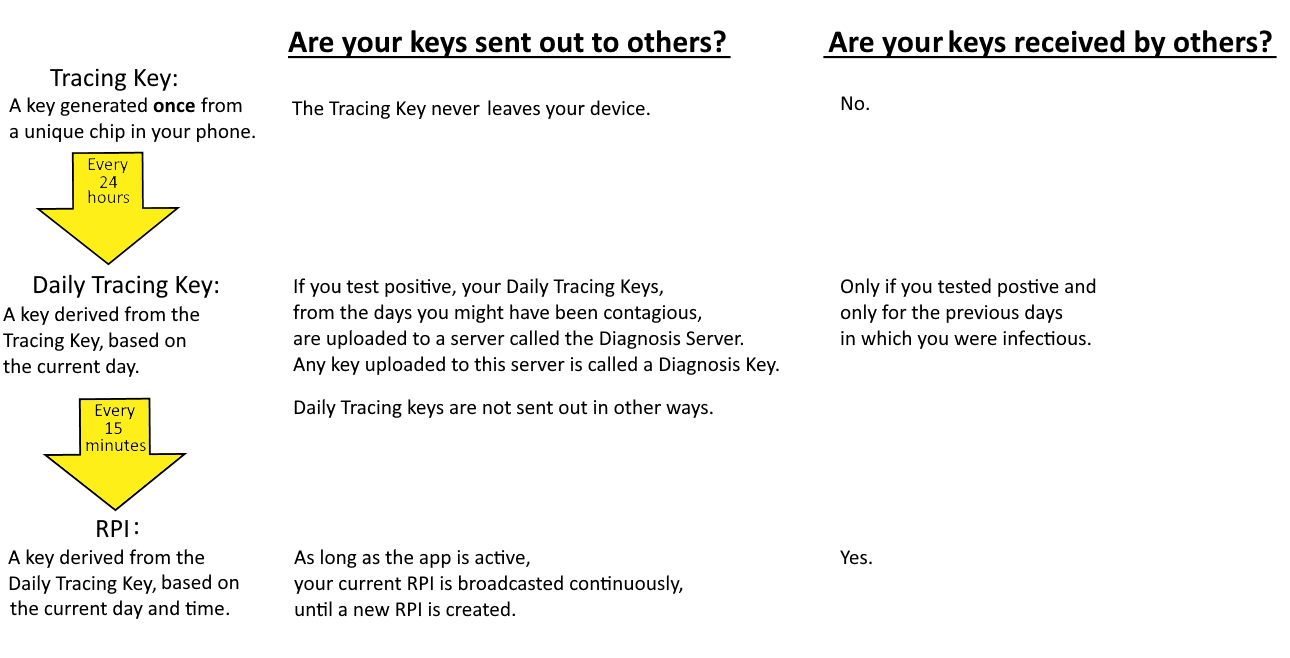

In order to figure out if you’ve been in contact with someone who, at that time, had corona, the app makes use of keys. These are not at all like the keys you use to unlock a door, but rather a piece of information that is stored digitally. You can think of them like a digital ID for your phone. The first time you start up your phone a unique Tracing Key is generated from a chip that is physically installed in every phone. Every day, another key is derived from this, known as the Daily Tracing Key. Every 15 minutes of every day, a final type of key is generated, known as the RPI. It’s the RPI that is broadcasted to other phones; the other keys are used for generating that unique key.

If you test positive for coronavirus, the Daily Tracing Keys you generated during the days you might have been contagious, are uploaded to a specific server. Any key uploaded to that server is called a Diagnosis Key and the server itself is called the Diagnosis Server. The Diagnosis Server does not store any other data from you. It’s basically like a pile of keys obtained from people with corona.

Your Tracing Key is not sent out. If it were sent out and someone got hold of it, they could generate all your Daily Tracing Keys and RPIs for every single day and 15 minute time frame; they could recognise the RPIs you send out and know if you’re near them. This is because every single Daily Tracing Key and RPI is generated the same way. It’s nearly impossible, however, to retrace the steps it takes to generate an RPI (or Daily Tracing Key) back to its original Tracing Key. So, for example, if someone receives two different RPIs from the same phone, they have no way of knowing they were sent by the same phone.

What does happen with these keys then? As long as the app is running in the background, it broadcasts the RPI to other phones. This broadcast is sent out about 4 to 5 times a second and is sent out via bluetooth; through waves, just like a Wi-fi signal.

Now, finally, when your device receives a broadcast from another phone, it stores the RPI along with a distance. This distance is the distance between the two phones. This is measured by measuring the strength of the signal that sent out the broadcast.

The app can count the number of RPI that are the same, in order to calculate the time you spent in range of that person. For example, if it receives one RPI five times, then the app knows you’ve been in contact with that person for about 1 second, since the RPI is sent out about 4 to 5 times per second.

Using a list of Diagnosis Keys, obtained from the Diagnosis Server, it derives from those a list of all the RPI for that particular day and 15-minute. It then checks if any of them match with the RPIs you received during that time frame. If this is the case, then that means that you’ve been in range of an infected person. It won’t send out an alarm just yet though. It first weighs the time you spent at each distance in order to conclude if you are at a significant risk of being infected. If so, it then let’s you know via notification.

Could the app prevent a full lockdown?

Could the app be the solution that prevents (or shortens) a lockdown? Will it keep our sport centers and schools open? Well, in order to be effective the app, the app needs to be used. We therefore asked some members of our audience who didn’t use the app, why they chose not to. Mia (15) said “de app werkt alleen als iedereen hem gebruikt” [the app only works if everyone uses it]. Gijs (15) said “Het gaat niet werken, want mensen blijven toch niet thuis als ze een waarschuwing krijgen.” [It won’t work because people won’t stay home, when they receive a warning.] Charlotte (14), on the other hand, wanted to use the app, but the app doesn’t work on her phone, since she has an older model. Other issues that might come up are people choosing to not test themselves, in which case the app doesn’t send out any warnings. And test or test results might come in very late, meaning the warnings might arrive too late too.

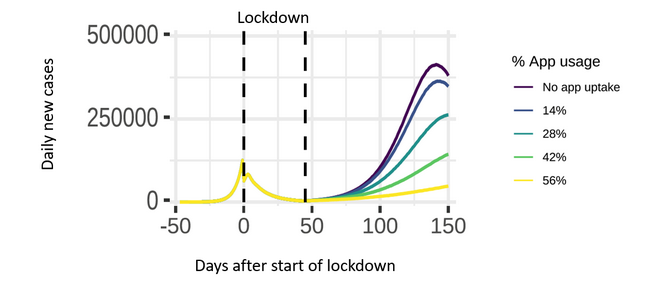

Does everyone need to use the app in order for the app to be effective? The Dutch Government said that if 60% of people use the app, then they would call the app a success. Does this mean that if only 59% of people use the app, the app is completely useless? Of course not! Even if only some people use the app, it could reduce the rate of infections significantly. A study from Oxford University concluded that “the app has an effect at all levels of uptake”. This means that, according to these projections, the app is still effective in reducing the amount of infections if much less than 60% of people use the app. More recent studies from Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Medicine and Google Research also reached the same conclusion.

The projected impact of app usage in the UK

From: ‘Effective Configurations of a Digital Contact Tracing App: A report to NHSX’ by Oxford University

So, in short, corona apps basically anonymously broadcast to and receive keys from other phones. These keys are then stored and later checked in order to find out if you were in contact with someone who could have given you the virus. Ultimately, all this data is thus sent back and forth to prevent a full lockdown. If a lot of people use the app, it could reduce the number of infections per day drastically. However, according to several studies, even if not a lot of people use the app, it is still effective in reducing the amount of infections.

Written by: Gerard van Beelen

Sources:

Contact Tracing Bluetooth Specification v1.1 for iOS and Android

Contact Tracing Cryptography Specification for iOS and Android

MIT Technology Review‘s Covid Tracing Trackers.

https://privacyinternational.org/explainer/3536/bluetooth-tracking-and-covid-19-tech-primer

https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/06/05/1002775/covid-apps-effective-at-less-than-60-percent-download/

https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2020-09-03-new-research-shows-tracing-apps-can-save-lives-all-levels-uptake

https://045.medsci.ox.ac.uk/files/files/report-effective-app-configurations.pdf

https://nos.nl/artikel/2332235-meerderheid-zou-veilige-corona-app-installeren.html