(Dis)Abilities in Sports

The (in)visibility of disability

Coverage and portrayal of disabled professional athletes in the media

By Mira Innemee, 14 April 2022.

You can probably name at least one athlete that won a medal at the Winter Olympic Games in Peking this year. But what if I ask you to name an athlete that won a medal at the Winter Paralympic Games? If you are struggling or have no idea, you are not the only one. But why is that? Limited media coverage of disabled athletes plays an important role in this. Think about it: when you turn on the TV during the Olympics, the NOS is broadcasting the Games almost every moment of the day. For the Paralympics, however, this is not the case. Last month, the Nederlandse Sportraad (Dutch Sports Council), revealed the advisory report, “Gelijkwaardig en Inclusief” (“Equal and Inclusive”). In its report, the council advocates for a new approach to achieve equality between Olympic and Paralympic sports and highlights several issues in current sports policies, as well as a lack of awareness and funding for disability sports. So, what exactly are these issues?

Competing for viewings and broadcast time

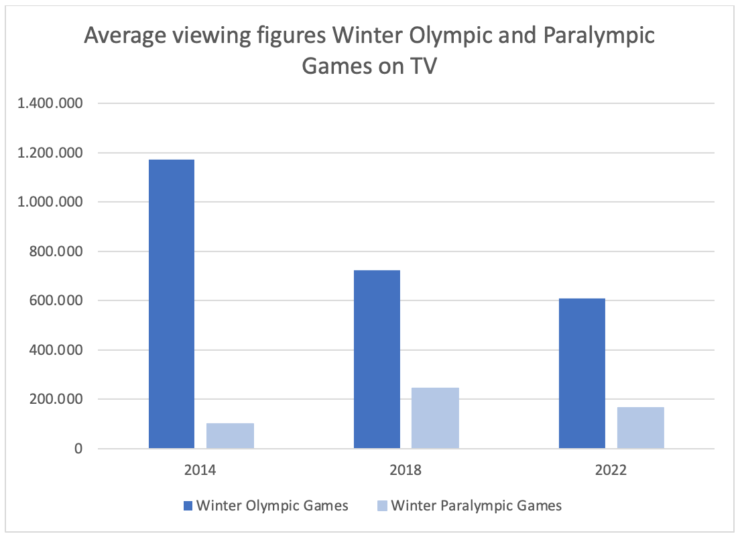

According to research that analyzed English language media in 11 countries, in 2020 and 2021, the Paralympics received only one tenth of the coverage of the Olympics. In the Netherlands, the viewing figures of the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games on TV in 2014, which represent the average number of people that watched it, show a similar pattern. Fortunately, the difference in viewing figures is a lot smaller in 2018 and 2022. However, the 2022 Winter Olympic Games are still watched about three times more often than the Winter Paralympic Games.

Average viewing figures Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games on TV in 2014, 2018, and 2022.

Still, Bo Kramer is positive. The 23-year-old professional wheelchair basketballer did not only win gold at the Summer Paralympic Games in Tokyo last year, but also became European Champion in 2021 and World Champion in 2018. She states: “Fortunately, media attention for disabled athletes has grown immensely over the past few years, but there is still room for improvement.” Given that the Paralympics still do not get the same amount of broadcast time as the Olympics, it seems that Kramer is right. During the Paralympic Games, generally only summaries with the highlights for each day are broadcasted on TV. Livestreams are available, but only on the NOS website.

Bo Kramer © Basketball experience NL

In contrast, the Olympic Games are live streamed on TV throughout most of the day. In addition, several TV programs give special attention to Olympic sports in which Dutch athletes are participating, such as ice skating. These programs have an extensive preview and discussion after the race, usually with experts. Why you hardly see this ever happen for a Dutch Paralympic athlete, you ask? The NOS states the following: “[…] For television there must be a broader interest for a specific game. We will – if the Netherlands qualifies – broadcast a couple of finales on NPO1.” However, interest from the public will become broader when people know more about the Paralympics, for which more broadcast time is an important aspect.

What can media do then? Kramer has ideas

So, the media need to step their up their game. As Kramer states: “It would help a lot if the NOS and RTL news would prioritize disabled athletes and their sports more. For example, when a disabled athlete gets a medal, it would be nice if it would be mentioned in the Achtuurjournaal (Eight O’clock News) together with some information about the sport. The more people see the sports and athletes, the more curious they will become. Besides, if people better understand the sport they’re watching, they usually enjoy it more, too.” Kramer’s last point can also be found in the before-mentioned advisory report of the Dutch Sports Council. In its report, the council states that although there is an increase in media attention for disability sports during the Paralympic Games, the attention quickly disappears when the event is over.

Another issue, according to Kramer, is money: “I think especially the difference between abled and disabled sports is the amount of money that comes from sponsors. However, when disabled athletes are more visible and if more people know about disabled sports, it is automatically easier to attract these sponsors.” Again, the Dutch Sport Council reflects Kramer’s concerns. The council states that it is common for Olympic athletes to receive support from sponsors for paying for their, often expensive, sports equipment. For Paralympic athletes, however, this is rarely the case. To bridge this gap, Kramer herself is also actively working to gain awareness, by doing interviews, being very active on social media, and by giving motivational talks at events.

Media portrayal: “supercrip” or “medicalized model”

Disabled athletes are not only less visible in the media, the way disabled athletes are portrayed in the media also is very different compared to their abled colleagues. According to the research of Rees, Robinson, and Sheets that specifically investigated media portrayals of athletes with a disability, descriptions of disabled professional athletes and their achievements commonly follow one of two narratives. The first is the so-called “medicalized model of disability”, where the athlete’s impairment is highlighted over their performance. The second is that of the “supercrip,” where the athlete is portrayed as someone that “achieved the unachievable,” despite their disability “problem”. When asking Kramer if she recognizes this, she immediately agrees: “Most of the time a news item starts with my disability, rather than about what I achieved. It would be a lot better if this is the other way around. I didn’t only win gold because of my disability, and I also don’t see my disability as a problem. I worked just as hard as all the other athletes, abled or disabled.”

All-in all, dominant media franchises play an important role and carry the most responsibility for providing more coverage and fairer portrayal of disabled athletes. But what can you do? When asking Kramer, she answers: “Talk about it, also with your kids. Have a conversation with someone that has a disability and ask your questions. Let’s change the definition of “normal” a little, not all people have two arms and two legs.”