Green on the Go

Does Bio-Asphalt Turn Out Better?

By Rebecca Kuijpers

Perhaps you have recently seen an article about the use of bio-asphalt in the Netherlands. This is being experimented with in more and more places in the Netherlands. In June 2021, for example, a 250-metre-long test section was constructed on the N987 between Siddeburen and Wagenborgen with completely plant-based asphalt. This bio-asphalt is seen as the asphalt of the future, but is this really the case? Project director of NG-Infra, Jenne van der Velde, has his doubts: “This asphalt contains less crude oil, but if it has to be maintained more often, it quickly becomes more polluting than the current asphalt.”

Differences

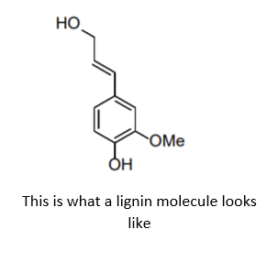

The biggest difference between ‘normal’ asphalt and bio-asphalt lies in the substances bitumen and lignin. Bio-asphalt uses the vegetable substance lignin, which can be used as a replacement for bitumen, a component of asphalt that is produced from crude oil. Lignin is released in large quantities as a residual product during, among other things, the production of paper. At present, the lignin is used in the factories as a fuel. This way it will not be thrown away. In recent years much thought has been given to the fight against climate change. Part of this is to reuse residual and waste products as well as possible. New

applications are therefore also being sought and found for the residual product lignin, such as bio-asphalt. The downside of this is, of course, that an alternative combustion product has to be sought when lignin is used in other places.

Test roads

In 2015, for the first time a piece of road was laid with asphalt in which lignin was used. In this experiment, a test road of 70 meters was laid, in which half of the bitumen in the asphalt was replaced by lignin in the top layer. In 2020, the first road was laid in Vlissingen in which lignin was incorporated in all three layers of the asphalt. Each layer of this road consists of asphalt with lignin, mixed with recycled asphalt. In June 2021, a piece of fully vegetable asphalt was even laid on the N987. On these stretches of road, the universities of Utrecht and Wageningen, among others, are now measuring how often bio-asphalt needs maintenance, how long it lasts and whether it can withstand different weather conditions.

According to Jenne van der Velde, the project director of NG-Infra, these test roads are desperately needed. NG-Infra is a partnership of infrastructure managers in the Netherlands. This organization brings together research and practice to develop the infrastructure of the future. To this end, they conduct research into various aspects of the infrastructure and then examine whether this is feasible in practice. Van der Velde explains that these test roads are an experiment in research into sustainable infrastructure. In the Netherlands, road maintenance is quite complicated. On average, the left lane in the Netherlands lasts about 17 years, but the right lane only lasts 11 years. This is because, for example, much more heavy traffic drives on the right-hand lane, which places a greater load on the asphalt. Lanes in the Netherlands are therefore often not replaced at the same time.

Not practical

‘If you replace one of the two lanes with bio-asphalt, all of that will naturally lead to practical problems,’ says Van der Velde. ‘You never know in which of the two lanes an emergency repair needs to take place, so you have to have twice as much material and equipment ready. One for normal asphalt repair and the other for bio-asphalt repair. So that is not sustainable at all. In addition, due to the different components of the asphalt, it does not have to be the case that the two types can lie next to each other at all. For example, you may get cracks between the two types of asphalt.’ He emphasizes time and again that a more sustainable composition does not have to mean more sustainable in general.

Replacing entire sections of road at once would also not be convenient, according to Van der Velde. ‘Then you have to throw away perfectly usable asphalt, which is a huge shame.’ It should be noted that we have previously laid a different type of asphalt on all roads in the Netherlands, so it is possible.

In addition to all the practical problems, although lignin can take over the adhesive function of bitumen, it cannot replace all components of bitumen. So there is still a need for petroleum in bio-asphalt. Research is underway at various universities into the replacement of the other components of bitumen. This is  now really being experimented with with the laying of the N987 between Siddeburen and Wagenborgen. In the future, research will have to show whether lignin asphalt is really more sustainable than our current asphalt. And what do you think? Will we be driving our electric cars on bio-asphalt in a few years’ time?

now really being experimented with with the laying of the N987 between Siddeburen and Wagenborgen. In the future, research will have to show whether lignin asphalt is really more sustainable than our current asphalt. And what do you think? Will we be driving our electric cars on bio-asphalt in a few years’ time?

Translated from Dutch.