Zoonoses: opening a can of worms

Infectious livestock

In 2020, researchers from Utrecht University determined that people living in a radius of 2 kilometres around a goat farm have an up to 55% higher chance of developing pneumonia. The cause of the relationship between goat farms and the increased risk of pneumonia is as of yet unknown. But other animals that we keep in the Netherlands for milk, eggs or meat can also form a risk for public health. How dangerous is our livestock actually? And what can we do about it?

The Dutch livestock mainly consists of cattle, sheep, goats, chickens and pigs. Like people, livestock can get sick from infections caused by for example viruses and bacteria. This is completely normal and in most cases not dangerous for humans. However, when the diseases can jump from animal to human it can be a risk to public health. We call these diseases zoonoses.

Goats have a bad reputation in the Netherlands when it comes to zoonoses. In early 2008, Q fever was diagnosed in goats from a large dairy farm in the province of North Brabant. Q fever is not only dangerous for goats, but also for cattle and sheep. In addition, thousands of people were infected and 95 died from the disease between 2007 and 2010. During that period, more than 50,000 goats were culled in the Netherlands alone. Fortunately, this is no longer necessary because goats are now vaccinated against Q fever.

Goats have a bad reputation in the Netherlands when it comes to zoonoses. In early 2008, Q fever was diagnosed in goats from a large dairy farm in the province of North Brabant. Q fever is not only dangerous for goats, but also for cattle and sheep. In addition, thousands of people were infected and 95 died from the disease between 2007 and 2010. During that period, more than 50,000 goats were culled in the Netherlands alone. Fortunately, this is no longer necessary because goats are now vaccinated against Q fever.

Why don’t we vaccinate all our livestock against all possible zoonoses? Researcher Dr Lidwien Smit of Utrecht University tells me that this is not always possible. For years, she has been involved in research on the consequences of livestock farms, and especially goat farms, on public health. “Especially animals that are kept for their meat are usually less likely to be vaccinated,” she tells during our conversation. “Because of trade agreements, meat cannot be sold abroad if it comes from animals that have been vaccinated”.

In addition, it often takes researchers a long time to discover the cause of a (new) animal disease and even longer to find a solution such as a vaccine. Researcher Dr Helen Esser of Wageningen University has been studying certain ticks that can spread zoonoses for years. “The Q fever bacteria primarily spread through air, but can also spread via ticks,” Esser tells in an interview. “Not only the tick and the pathogens in the tick must then be examined, but also the area in which the tick lives and the climate at that time, for example”. Questions that scientists try to answer with their research are for example: Are there more or less ticks in warm weather? And do more or less people then become sick? “Only when we understand why certain diseases break out in certain places can we do something about it,” says Esser.

It is not surprising that in recent decades more zoonoses emerged, says Esser. According to her, it is time we stopped pointing to animals as the culprits for the emergence of zoonoses and took a critical look at ourselves. “Because we keep our livestock with great numbers in one barn, and because we travel around the world and trade in wild animals, we create opportunities for pathogens to quickly spread around the globe”. This makes the chance of a pandemic emerging greater than before.

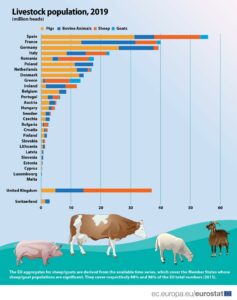

It is therefore important that we keep a close eye on the emergence of new zoonoses throughout the world. Yet, the Netherlands in particular is sometimes called a ‘ticking time bomb’ in regard to zoonosis. Migratory birds, for example, like to take breaks in our little country during their journey south. As a result, the bird flu virus annually spreads across poultry farms across the country. However, our livestock creates the biggest risk in relation to zoonoses. But when you take a look at the table below you can see that many other European countries have the same amount or even more animals than the Netherlands.

Why does the Netherlands poses such a risk? The problem lies mostly in the size of our country. Because the Netherlands is so little, we keep a relatively large amount of animals on a small area. In addition, a lot of people live in the Netherlands leading to large groups of people having to live close to large farms. This is in contrast to bigger countries where farms are built far away from cities.

The effect of livestock farms on residents is being monitored since 2009 in the Netherlands by the RIVM. Smit for example contributed to mapping the locations and sizes of livestock farms. Moreover, she works on calculations to predict the risk of living close to a stable. Because fact is that stables can be sources of zoonoses.

According to Esser, the zoonosis problem with the Dutch livestock is twofold: “Firstly, there are far too many animals being kept in one barn. Where goat farms used to be small, we now have stables with thousands of goats together. This is a paradise for zoonotic pathogens, which spread best when there are many hosts together”. The second problem is that the animals are genetically very similar. If one animal can become sick, this means that almost all the animals in the stable can and will become infected. As a result, a disease outbreak leads to the (precautious) culling of hundreds to thousands of animals. In Esser’ opinion it is important to reduce the number of livestock in the Netherlands. In that way, animals will have more space in their stable, and will the chance of disease emergence be smaller.

However, according to Smit, many rules have been put in place to prevent the Netherlands from becoming a ‘breeding ground’ for zoonoses. She points out that the Dutch livestock industry is more developed than in many other countries. From her own experience, Smit says: “Last year, when a farmer saw that a number of his minks were sick, he immediately rang the alarm bell. Animals were sent to the Animal Health Service, where scientists concluded after only two days that the minks were infected with COVID-19”. After that it did not take long before action was taken and all mink farms in the Netherlands were eventually culled. This shows how well animal diseases are monitored in the Netherlands. Smit also explains that hygiene measures in Dutch livestock farms are strictly followed to prevent the spread of pathogens. According to Smit, keeping a close eye on the animals and maintaining strict hygiene can prevent the emergence of a risk to public health.

The large number of animals in Dutch stables thus certainly increases the risk of (new) zoonotic outbreaks. This is mainly because animals and people live so close to each other in the Netherlands. On the one hand, Smit told us that the spread of such diseases is limited by the strict measures in place in livestock farms. On the other hand, however, Esser points out that preventing the diseases from emerging in the first place is the best approach. To achieve this, the Dutch livestock population must be reduced. If animals have more space in the stables, the chances that many of them become are smaller.

References: