Puberty

Boys follow in girls’ footsteps in HPV vaccinations

By Tessa Vreeman, April 13 2022

Since this February, boys have also been invited for vaccination against the human papillomavirus, also known as HPV. Given that the HPV vaccine was previously only available to girls and was known as the cervical cancer vaccine, this raises many questions among parents. Therefore, as of April 11, the Twijfel Telefoon (doubt phone) – the phone number previously used as the Corona Vaccination Phone – is open for all questions about HPV. Since the introduction of the vaccine in 2010, more knowledge about the vaccine and its effects has been accumulated, both in the Netherlands and abroad. How are the vaccines doing now in girls and how can they protect our boys as well?

Photo by @isengrapher via Unsplash

HPV vaccine gives promising results

The HPV vaccine protects against HPV infections, these are transmitted through sexual contact and can cause cancer if infections persist. In 2010, the vaccines were introduced into the National Vaccination Program of the Netherlands. Since that time, several scientists have done a lot of research on the efficacy of the vaccine. Results on the direct effectiveness of the HPV vaccine are long in coming. This is because the development of cancer after persistent HPV infection can take years and thus cannot be measured directly.

Nevertheless, some long-term studies are already underway that show promising results. ‘There are all kinds of studies being done by the RIVM in which girls who were vaccinated at the time are still being followed – the so-called HAVANA study,’ mentions Teelen, campaign manager of the HPV campaign at the RIVM. The HAVANA study has now been running for fourteen years, with nearly 2,000 women donating blood and a vaginal smear annually for the study. ‘In this we see an increasing protection against HPV,’ says Teelen.

‘However, the first girls who are vaccinated will not be invited for the population screening for another two years,’ Teelen mentions. In the Netherlands, women aged 30 and over are invited for the population screening HPV. A smear is then taken and tested for cervical cancer or its pre-cancerous stage. Once these tests have been carried out on the women in our population, we can really see on a large scale whether the HPV vaccination actually causes less cancer.

In England, they are already one step ahead. In 2008, vaccinations started for 12-13 year old girls and population studies in England start as early as age 25. Now, 14 years after the start, the first vaccinated women have already been invited for screening. In November 2021, an article from a group of researchers from England was finally released where they compared the data of vaccinated and unvaccinated women.

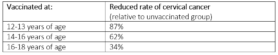

The researchers from London set up 4 large groups with data from a database: unvaccinated, vaccinated at age 12-13, vaccinated at age 14-16 and vaccinated at age 16-18. They compared the results of the population study, looking at cervical cancer or its pre-cancerous stage. This showed that the vaccine against HPV is very effective and works better when vaccinated at a younger age.

Table: Results from the November 2021 UK study in which the researchers looked at data from the population screening. This shows that there is a reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer upon vaccination.

Not only against cervical cancer

As campaign manager, Teelen was commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport to set up the current campaign for the HPV vaccination. The campaign had to be redesigned and the team threw the term ‘cervical cancer shot’ out the door. The new slogan is now: protected against six types of cancer with one vaccine. HPV also plays a role in five other cancers, including cancer of the head and neck, the penis and the anus. A shot against HPV infections therefore does not protect only girls or women, nor does it protect only against cervical cancer.

Transmission of the virus can occur with any form of sexual contact and is highly contagious. 80-90% of all men and women will get an HPV infection at least once in their lifetime. This infection is cleared by the body in most cases. However, with long-term infections, the DNA of the virus can be incorporated into the body cells. These cells change and will grow faster, which can lead to tumours. In the Netherlands, 1,100 women and 400 men are diagnosed with a cancer caused by HPV every year.

The HPV vaccine works best before a person has come into contact with the virus. When vaccinations started in 2010, the RIVM decided to vaccinate from the age of 13, because they were uncertain about the duration of protection. The Health Council has now conducted further research, which shows that the vaccine is still effective in all girls who were vaccinated at the start. The vaccination age has therefore now been lowered to 10 years.

Parents are very important in the HPV campaign: until the age of 12 the decision about the vaccination lies with the parents. However, Teelen believes that a joint decision is important: ‘You should also discuss it with your child.’ Research by Teelen’s campaign team showed that parents often think their children are too young for the HPV vaccination. They associate the shot with sexual behaviour, something their 9-10 year old child is not yet engaged in. This is, of course, very understandable, but also the very reason that the shot is now offered at an earlier age. ‘The vaccine doesn’t work for existing infections, it only works for future infections,’ says Teelen. The earlier the better, which is what the British study also demonstrated.

In conclusion, it is very important that boys are vaccinated. It protects them against various types of cancer, but also contributes to the group protection of the population. The Health Council expects the effectiveness to be similar and even greater for the population because of that group protection. We will take the experience that has already been gained in women with us for future research in men. Hopefully we will soon have put behind us the idea that an HPV vaccine is exclusively for girls and together we will be on our way to a healthier population.

Sources

De Twijfeltelefoon.

https://twijfeltelefoon.nl/

Vaccinatie tegen HPV | Advies | Gezondheidsraad. https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2019/06/19/vaccinatie-tegen-hpv

HPV-kanker | Rijksvaccinatieprogramma.nl.

https://rijksvaccinatieprogramma.nl/infectieziekten/HPV

Vaccineren tegen HPV-kanker | Rijksvaccinatieprogramma.nl. https://rijksvaccinatieprogramma.nl/vaccinaties/hpv

HPV – Humaan Papillomavirus | RIVM.

https://www.rivm.nl/hpv-humaan-papillomavirus

Hoes, J., Pasmans, H., Knol, M. J., Donken, R., van Marm-Wattimena, N., Schepp, R. M., King, A. J., van der Klis, F. R. M., & de Melker, H. E. (2020). Persisting Antibody Response 9 Years After Bivalent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination in a Cohort of Dutch Women: Immune Response and the Relation to Genital HPV Infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 221(11), 1884–1894. https://doi.org/10.1093/INFDIS/JIAA007

Falcaro, M., Castañon, A., Ndlela, B., Checchi, M., Soldan, K., Lopez-Bernal, J., Elliss-Brookes, L., & Sasieni, P. (2021). The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. The Lancet, 398(10316), 2084–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02178-4

Szymonowicz, K. A., & Chen, J. (2020). Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biology & Medicine, 17(4), 864. https://doi.org/10.20892/J.ISSN.2095-3941.2020.0370