Dangerously Endangered

Proper Wildlife Etiquette: The success of a well-mannered animal

Author: Laura Anne Kuipers

Do the names Mountain Mist Frog, Yangtze Sturgeon and Chinese Paddlefish ring a bell? These are 3 animal species that were declared extinct in 2022 by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources). And what about the European Bison, Eurasian Beaver or the Bittern? These are 3 animal species that were extinct in Europe, but not anymore! After being bred in captivity and returned to their natural habitat, populations are rising and nature is thriving. There are many species facing extinction, and for some, the highly complex method of captive breeding is the only solution left for survival.

Animals that risk extinction need support in numbers. Remaining populations may be significantly small, or their habitat is threatened by climate change or illegal activities. Removing these species to a safe captive environment, while restoring safety in their original home, is often the best or only solution to prevent extinction. But as you can imagine, a captive setting is very different from their natural habitat.

In some cases, a captive environment can cause a lot of stress. The Norwegian Institute of Nature Research and the University of Oslo launched an ongoing captive breeding program of the endangered Arctic Fox in the year 2000. Due to non-optimal conditions of the captive environment, the females were not in the mood to breed for the first two years! After being moved to a larger area, more reminiscent of their natural home, their stress cleared and breeding improved drastically.

But what happens once the animals go back home? How does a change in environment impact these animals and their newborns, who have never experienced the place they actually belong?

The bare necessities

Animals learn the means for survival, just like us, through their environment and social construction within colonies. How to find food? What foods are even safe to eat? Some behaviours are innate, like the recognition of predator shapes and fur-patterns, but many essential skills need to be learned by watching their adult peers.

One of the most important aspects of wild etiquette is how you handle danger, in particular predators. Anne Marijke Schel, assistant professor and researcher in animal behaviour and ecology, illustrated a fascinating example on finer communication elements in predator recognition. “The Green Vervet Monkey is known for their diverse predator behaviour, as they make different sounds for each predator. When the alarm is sounded for an eagle, everyone should know to hide in the bushes on the ground. They make a different noise for leopards, then everyone knows to get back into the trees as quickly as they can.” Understanding the meaning of each noise is learned by doing and observing, and is necessary for survival.

“When you release an animal, you don’t want them to eat something dangerous or be eaten by something dangerous on the first day.” – Anne Marijke Schel

Animals who have no experience with certain aspects of the area where they are reintroduced, need to be trained in correct behaviour to be able to survive. But besides behaviour, there is also another important factor that dictates an animal’s survival: physical health.

Survival of the fittest

Have you heard the beautiful love story of Omid and Roya? Omid was a lonely Siberian Crane male, flying from Siberia to Iran (4546 kilometres) each year looking for a mate. Since he was the last of this specific crane species, no one answered his calls for 15 years! Then he met Roya, a female. And after some bickering, because Roya kept stealing his food, they fell in love. However, Roya was captive-bred in Belgium. Since she is not used to the wild way-of-life, her wings might not be strong enough yet to travel all the way back to Siberia with Omid this spring for the breeding season.

Strength is just one example of physical health that can influence an animal’s survival. But there have been cases where even complex bodily functions changed due to a captive environment. A team of researchers in China studied captive breeding in the critically endangered Pangolin (2022), and discovered a cause for early deaths after release in the wild. A difference in gut microbes from their wild elders, made the young Pangolins extremely sensitive to diarrhoea and infection!

The beauty of complexity

I can hear you thinking, if this is such a complex method why should we bother? Do we really need to save every single species? Merijn van Leeuwen, the coordinator of the Amazon and Atlantic forest for WWF, summarised the essence of species preservation like this: “A healthy ecosystem is a complete ecosystem, filled with species who belong”. The complex relations between plants, animals and their surroundings are necessary for a healthy planet.

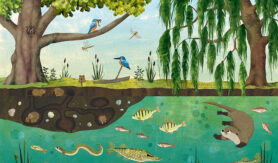

A beautiful example of these complexities is Yellowstone, a national park in the United states that was once struggling due to the absence of a vital role in the ecosystem: the wolves. After all of them being killed in the 1930’s, a team of biologists reintroduced the wolves back to Yellowstone 30-35 years ago. The return of this predator resulted in restoration of greenery and an increase of trout in the rivers. Sounds strange right? As the wolf induced fear, the wapiti would avoid the river banks because they are most vulnerable there. Birch and Willow trees along the banks got a chance to grow, attracting beavers. And beavers do what beavers do best, build dams. The dams resulted in improved water quality and creation of little lakes along the rivers course, breeding grounds for the trout. Even when not connected at first glance, every species within an ecosystem is a valuable piece of nature’s puzzle.

Captive breeding requires detailed planning in replicating the natural environment, securing the animals physical wellbeing and also including their social needs. But when done right, it can be the solution in restoring nature. Since wildlife populations have seen a devastating 69% drop since the 1970’s, according to WWF’s Living Planet Report (LPR) from 2022, we have a duty to assist nature in bouncing back. When we pay attention to what each individual species needs to survive before releasing them into the wild, we are on the right track in helping them rebuild.

In the mood for some good news on captive breeding? Here are some success stories from 2022:

Britain’s loudest bird bounced back after almost going extinct twice! Bitterns can be as loud as a jet aeroplane taking off, but England is very happy with this noise as their numbers are now in hundreds and are reaching further north than has ever been recorded.

Beavers are back in London after 400 years! They were hunted to extinction centuries ago, reintroductions helped restore biodiversity and even mitigate flooding impacts.

Beavers are back in London after 400 years! They were hunted to extinction centuries ago, reintroductions helped restore biodiversity and even mitigate flooding impacts.

The rare parrot species from the movie RIO has been reintroduced to its forest home 3 years after being declared extinct in the wild. Successful breeding attempts in Germany are planned to be moved to Brazil this year to further continue!

The rare parrot species from the movie RIO has been reintroduced to its forest home 3 years after being declared extinct in the wild. Successful breeding attempts in Germany are planned to be moved to Brazil this year to further continue!

[References]

IUCN red list of threatened species – https://www.iucnredlist.org/

The endangered Arctic fox in Norway—the failure and success of captive breeding and reintroduction. September 2017, Polar Research 36(sup1):9. DOI:10.1080/17518369.2017.1325139

International crane foundation – A dream for hope (21st february 2023) https://savingcranes.org/2023/02/a-dream-for-hope/

Differences in gut microbes in captive pangolins and the effects of captive breeding (Wenjing Jiao et al, december 2022) http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1053925

World Wide Fund for Nature – Living Planet Report 2022 – https://livingplanet.panda.org/

Natural History Museum – The conservation success stories of 2022. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/january/conservation-success-stories-2022.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.