The plastic trash clash

New invention mimics plastic dispersal in the ocean

By Emma van den Bergh, 4 April 2022

There’s more plastic in our sea than there are stars in the galaxy! This English slogan is about the plastic soup: the collective name for all the plastic that accumulates in the great waters and proverbially indicates that there is more plastic there than stars in our universe.

Scientists all over the world are doing more and more research into the role of ocean currents on the distribution of plastic. Researchers at Utrecht University are now developing a new computer programme called ‘The Particle Trackers’. This programme can show how plastic spreads in the ocean by means of an animation in the form of a 3D map. This project took part in a competition (the Blue-Cloud Hackathon) in February 2022 with which they won the main prize of 25,000 euros. With this money, the Utrecht researchers can now actually develop the computer programme.

What is plastic soup?

Source: https://plasticsoep.sites.uu.nl/

The discovery of the plastic soup goes back to 1997, when Captain Charles Moore crossed the big ocean from Hawaii to Southern California. Miles away from civilisation, he saw pieces of plastic floating around his boat. Moore described this discovery as plastic soup and this term is still used today.

But why hasn’t the problem of plastic soup been solved (yet)? This is because all the plastic that has ever been produced still exists. Plastic does not decay, but breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces. These large and small pieces of plastic remain and are harmful to nature. All the plastic that ends up in the ocean is carried along and accumulates where the ocean currents take it.

Influence of ocean currents

In an attempt to tackle this problem, scientists are doing a lot of research. One of the Netherlands’ best-known ocean scientists is Erik van Sebille, a researcher at Utrecht University. He has been researching ocean currents and how plastic spreads around the world for years.

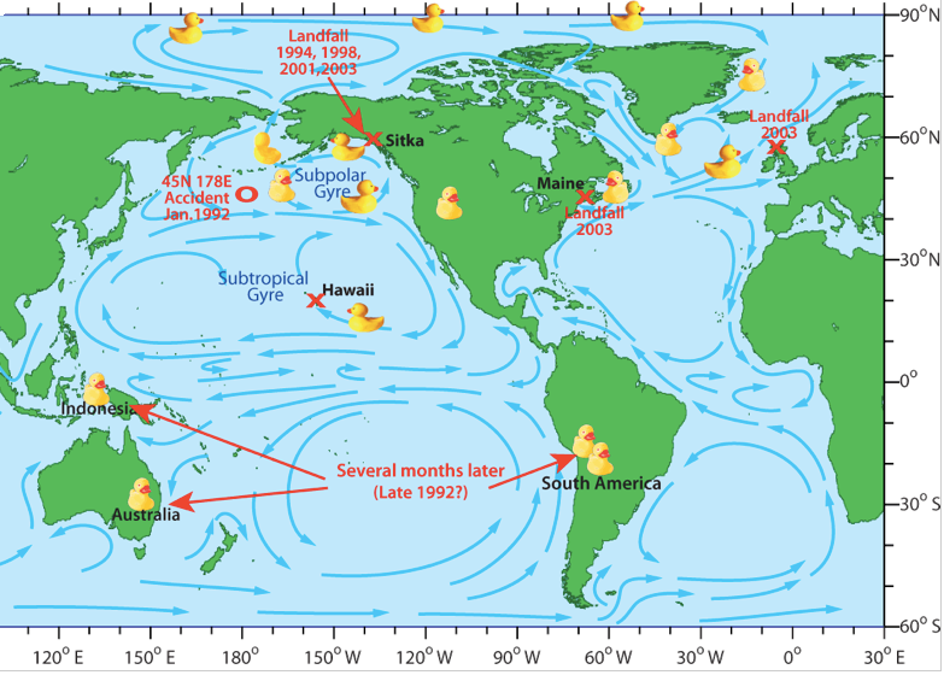

It may sound strange, but yellow rubber ducks have contributed to our understanding of ocean currents. In 1992, a container containing 28,000 plastic rubber ducks fell overboard from a Chinese cargo ship. The ducks were found all over the world, revealing for the first time how plastic spreads across the surface of the ocean.

The movement of rubber ducks through the ocean. Source: SEOS-project.

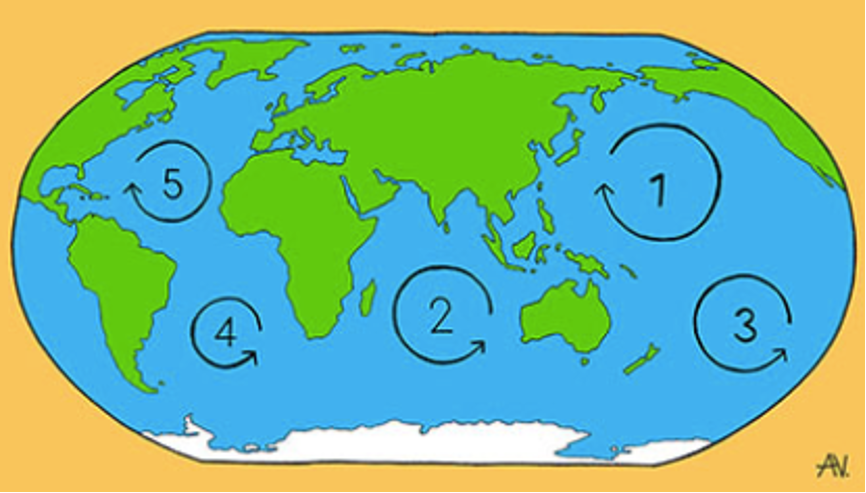

Plastic therefore spreads by ocean currents. In total, there are 5 strong currents that influence the movement of the plastic. These are called gyres, and are ring-shaped.

The five gyres are:

1) the North Pacific gyre;

2) the Indian Ocean gyre;

3) the South Pacific gyre;

4) the South Atlantic gyre and

5) the North Atlantic gyre.

The five gyres. Source: https://plasticsoep.sites.uu.nl/

Water in the gyre moves towards the centre of the flow circle, and here it flows downwards into the depth. The rotating movement of the water carries the plastic to the centre of the gyre. Only where the water is sucked into the depth with the current, the plastic remains floating in the centre of the gyre. This creates ‘islands’ of plastic with an average quantity of plastic of 10 kilograms per square metre on the surface. Although, according to Van Sebille, these are not islands, but rather parts of the ocean with a ‘higher density of plastic’.

New invention

Van Sebille and two researchers from his team, Delphine Lobelle and Claudio Pierard, talk about the influence of ocean currents on the plastic soup and the computer programme they are developing.

“We have to find out where all the plastic is before we can study the impact it has on aquatic life” – Erik van Sebille

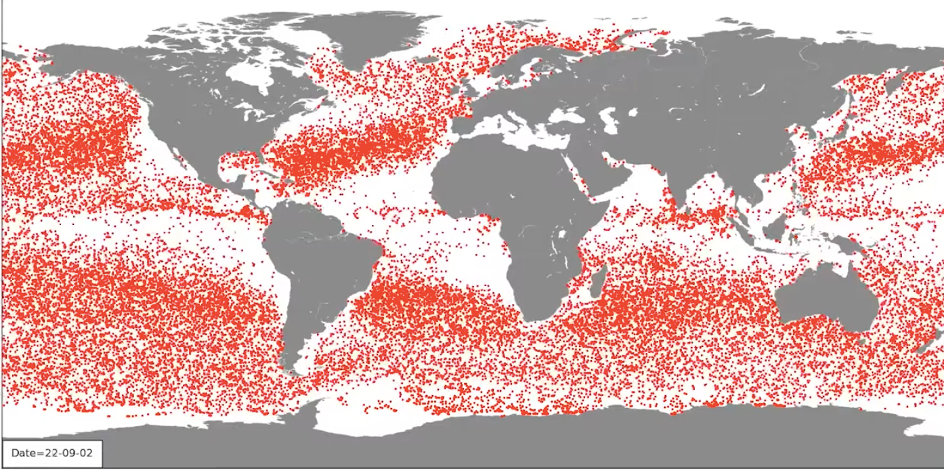

After years of research into the plastic soup, it is now known that a maximum of 1% of all plastic floats on the surface. But where the other 99% of the plastic has gone remains a mystery. This is one of the big questions that Van Sebille is trying to answer together with his research team ‘TOPIOS’. Using a computer programme, they made an animation that imitated the movement of plastic in various places in the ocean; on the surface and in depth.

The programme that the researchers are currently using for this is OceanParcels. Pierard explains: ‘In this programme, we use information about plastics, ocean currents and even climate to make an animation that depicts the distribution of plastic particles across the ocean surface’. Unfortunately, it does not map the deeper layers of the ocean. Therefore, Van Sebille’s research team has started a new project: the making of a 3D map that can follow plastic through the entire ocean.

Plastic distribution in the ocean as simulated by TOPIOS. Source: http://topios.org/

Lobelle, who will lead the TOPIOS project, says: ‘We are building on existing designs and want to use the movement of water in our programmes. This will allow us to closely monitor large areas of water. We will take sedimentation, fragmentation, stranding, wave mixing and uptake by living organisms into account, as these factors affect the spread of plastic’.

This programme can calculate a 3D map of different sea currents, coastlines and living organisms,’ says Pierard. With these measurements, they will describe a wide variety of scenarios that can be used to test different propositions about plastic diffusion. They will also determine where the risk from plastic pollution has the greatest impact.

Ultimately, Lobelle and the research team hope to influence policy makers on a national and international level. With this programme, she wants to inform the general public about which countries are responsible for which part of the plastic problem and hopefully in the future will inform engineers about how and where they can best invest resources to reduce plastic dispersion in our ocean. This is in line with the goal of Van Sebille, who finds it important to involve the general public in his research and to explain the science behind plastic dispersion in the ocean.

In summary, plastic soup is not a problem that can be easily solved. But by doing more research, we are learning different ways to approach the plastic problem. One of these ways is to use computer programmes to simulate the movement of plastic with a 3D map, in order to detect the missing 99% of plastic.

Would you like to take action yourself? On 8 June it’s ‘World Ocean Day’ and all over the world actions are started to clean up plastic. Take a look at https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org and see what you can do!

Sources

Websites:

All About Plastic Soup. (2022). Universiteit Utrecht. Geraadpleegd tussen 12 en 16 maart 2022. https://plasticsoep.sites.uu.nl/en/

Erik van Sebille. (2022). Universiteit Utrecht. https://www.uu.nl/medewerkers/EvanSebille

Plastic Soep Foundation. (2022). Geraadpleegd tussen 12 en 16 maart 2022. https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org

TOPIOS. (2022). Geraadpleegd tussen 12 en 16 maart 2022. http://topios.org

Interviews:

Leden van onderzoeksgroep TOPIOS, Universiteit Utrecht: Erik van Sebille, Delphine Lobelle, Claudio Pierard.

Afbeeldingen:

Stevige PLASTIC SOEP: https://plasticsoep.sites.uu.nl/en/

Badeendjes: https://seos-project.eu

Gyres: https://plasticsoep.sites.uu.nl/en/

Plastic deeltjes: http://topios.org