Archief

Could pig kidneys eliminate the donor waitlist?

Would you be open to receiving a pig kidney if you needed one? No, it won’t make you start oinking like Peppa pig. All jokes aside, in the USA alone every day 17 people die waiting for an organ transplant and over 100.000 people are on the waiting list, 85% of which need a kidney. This can’t be solved with good policy and current medical practice alone. There might be another solution: in July 2023 a team of NYC medical researchers took the next step. A pig kidney they transplanted survived and functioned for over a month, in the living body of a brain dead man. They took a kidney from a genetically modified pig, that made it more compatible for transplantation to a human.

Before we move on to the science behind this discovery, I would like to tell you about a kidney patient. Because we shouldn’t lose sight of who we are trying to help. Kitty Jager is 51 years old, loves to walk her dog, works fifteen hours a week and wants to keep going on holidays. She tries to postpone getting hemodialysis: getting hooked up to a machine to filter her blood at least three times a week for four hours per session, for as long as possible. “You can live, but you can’t do everything (on dialysis)” she said. She only has 6% kidney function remaining, which means her kidneys are not able to filter waste products from her blood sufficiently. Usually patients start dialysis when they have 15% or lower kidney function. “I try to really focus on what I can do” She says. But every morning is a gamble whether she wakes up with enough energy to function normally or not. Her condition gets worse over time. Eventually she must go on dialysis if her kidney function reduces further or, without a kidney transplant, she will die.

One of the options for a kidney patient is receiving a transplant from a living relative. Kitty’s sister offered their kidney. “I chose not to receive a kidney from a loved one, that is too big (of a gift) and very emotionally complicated for me” she elaborates, “I already have mixed feelings receiving a small gift, let alone an organ”. She chooses to wait for a “dead” donor, a donor who has put a kidney up for donation after their death.

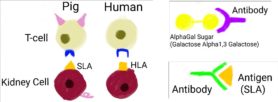

The donor kidney needs to be matched. Her blood type and that of the donor must be compatible and the HLA-markers (Human Leukocyte Antigen) should be as close as possible. Without a perfect match her own immune system may start rejecting the organ in two ways; by making antibodies against antigens presented by HLA for instance and/or because T-cells, a type of immune cell, can destroy cells with mismatching (foreign) HLA-markers. Rejection (slowly) leads to organ failure. It is nearly impossible to find a perfect HLA match besides being identical twins.

The organ of the donor needs to be harvested from of the body, preserved and transported as quickly as possible to Kitty. She will then undergo major surgery and for the rest of her life she will need immunosuppressants, a type of medication to prevent rejection. The average waiting time for a kidney transplant is 2,2 years in the Netherlands.

In 2020 the donor law was introduced in the Netherlands, to reduce the donor waitlist time by automatic registration. This was successful in increasing the amount of available organs, but the demand has also risen. Kitty often heard people around her saying “oh yes, I should really register but I haven’t made the time for it yet”. She is very happy about the automatic registration and supports this by saying “As long as you have a choice (to de-register)”.

After a person dies their organs start to deteriorate, which goes even faster when they’re taken out of the body. During transport they become unusable within 9 hours. Researchers are trying to increase the preservation time in various ways. Increasing this long enough would allow for an organ bank to be built, which would drastically shorten the waitlist.

Transplanting a thymus, an organ involved in the immune system, alongside a kidney could reduce the need for immunosuppressants. In 2021 a baby received a heart and thymus transplant. “With the donor thymus, the recipient can make T-cells that recognize the donated heart as its own, reducing the chance of rejection.” doctors of Duke university hospital say.

Unfortunately these current strategies are not enough to eliminate the donor waitlist. Research into new techniques has to be done. Like Xenotransplantation, transplanting across species. Before pig kidneys were transplanted to humans, they were first transplanted to non-human primates. That has now been done many times, like the pig thymokidney transplanted to a baboon that functioned for over 80 days. A pig kidney was successfully transplanted to a human for the first time in September 2021 by a transplant surgeon and his colleagues at New York University. At that time the ethics board gave permission to test it for 54 hours. Usually in medicine the allowed time gets prolonged after a successful study.

Why use a pig’s kidney?

Pigs have a blood type which can be matched to humans (OA instead of ABO) and their kidney anatomy is similar as well. There are also reasons not to use pig kidneys. Regular pigs have an Alpha-gal gene which results in a type of sugar present on the cell surface that humans can make antibodies against. That’s why the pigs used in July 2023 were genetically modified not to have this gene present, Gal-safe pigs. Tissue from the thymus of the pig was also transplanted, to supplement T-cells. In the long term our body can still have a strong immune reaction against any type of pig protein recognized as an antigen, like SLA (Swine leukocyte antigen).

Figures:

Human T-cells can recognize pig kidney cells as foreign by their SLA with the dark blue receptor (TCR). Antigen presenting and B-cell immune cells are involved in foreign antigen recognition and antibody production. When the antibodies bind to the foreign cells antigens, acute vascular rejection or chronic rejection takes place.

Before this treatment could become widely available, first a pig kidney and thymus have to be transplanted to an otherwise healthy kidney patient. That would solve the donor waitlist problem right? Well no, Kitty said she would never take the life of an animal to prolong her own. She is against organ farming. “Pigs are very intelligent animals and the bio-industry is horrific” she said. She participated in a donor dialogue where another patient said “I don’t care where the kidney comes from, if it works it works”. Kitty respects others choices, she values the right of medical self-determination like the highest good. But she is against the formation of an industry that farms animals for their organs, not against patients making use of it to survive. She would prefer that attention is focussed on animal cruelty free methods and preventative medicine. In the future she hopes 3D-bioprinting with her own cells could create a kidney. Then she wouldn’t have to take immunosuppressants nor an organ from anyone else, human or pig. Another group of patients who might be left out are muslim, who don’t consume pig meat. Even though the pig kidney xenotransplantation research might seem promising it’s clear this won’t be a one size fits solution.

Supplemental reading

- Ethical concerns of current kidney transplantation (15)

- Humanising and dehumanising pigs in genomic and transplantation research (17)

- Growing kidneys on extracellular matrix (ECM) (10)

- Regenerative medicine, immunosuppression free transplantation: 3D printing biofabrication, embryonic stem cells, tissue engineering (9)

- Human-pig hybrids, putting stem cells in pig embryos (11)

Sources

- https://www.donors1.org/learn-about-organ-donation/who-can-donate/get-the-facts/

- https://www.newscientist.nl/nieuws/getransplanteerde-varkensnier-in-hersendode-man-werkt-na-ruim-een-maand-nog-steeds/

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-kidney-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20354521#:~:text=And%20as%20kidney%20disease%20progresses,too%20much%20or%20too%20little.

- https://health.ucdavis.edu/transplant/livingkidneydonation/matching-and-compatibility.html

- https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/immuno#:~:text=of%20the%20drugs.-,Does%20everyone%20who%20gets%20a%20new%20kidney%20have%20to%20take,you%20to%20have%20a%20rejection.

- https://nierstichting.nl/nierdonatie/feiten-en-cijfers/#:~:text=Eind%202020%20stonden%20er%20in,wachttijd%20is%202%2C2%20jaar

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/novel-heart-thymus-transplant-technique-may-spell-end-of-lifelong-drugs#The-future-of-organ-transplants

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35595989/

- https://bjssjournals-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.11686?sid=worldcat.org

- https://www-nature-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/articles/s41592-019-0325-y

- https://www.newscientist.nl/nieuws/voor-het-eerst-zijn-menselijke-nieren-deels-gekweekt-in-varkens/

- https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/science/article/pii/S0041134510007700

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22565997/

- https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-its-kind-intentional-genomic-alteration-line-domestic-pigs-both-human-food

- https://www.nvn.nl/nieuws/orgaandonatie-volgens-filosoof-ellen-ter-gast/

- https://www.medschool.umaryland.edu/news/2023/Lessons-Learned-from-Worlds-First-Successful-Transplant-of-Genetically-Modified-Pig-Heart-into-Human-Patient-.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9684229/

- https://www-sciencedirect-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/science/article/pii/S0140673623013491

- https://nierstichting.nl/nieuws/2023/01/nieuwe-donorwet-succesvol-aantal-niertransplantaties-fors-gestegen/#:~:text=%E2%80%9COnder%20de%20nieuwe%20Donorwet%20zien,groep%20pati%C3%ABnten%20op%20de%20wachtlijst.

- https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/extending-preservation-time-donated-livers

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8549459/

U moet ingelogd zijn om een reactie te kunnen plaatsen.